Wait, do you think of THIS during rond de jambe?

Thigh bones. Circular movement. And Leonardo Da Vinci's Vitruvian Man.

Every ballet class, no matter where in the world or what language, follows a consistent structure. We do plies at the very beginning of the barre, then tendus from first position, tendus from fifth, degages, rond de jambes, fondus, frappes, adagio, and then grand battements. This should all sound familiar! Unless you are doing Cecchetti class, then you might be starting from grand battements…

So why do we do it in this order?

Plie is important because we are checking/warming up by bending all of our joints, and using appropriate muscles to do that.

Tendu in first is important for turn out, because we can work the outside of our hamstrings and isolate them from the inner hamstrings.

Tendu in fifth is when we introduce the tiniest movements to front and back, which is important because everything we do should have the direction of front, side, and back to be dynamic. It is very important to know how to do tendu to the front, side, and back accurately with appropriate muscles to set up the rest of the class right.

Degage is when we start adding speed to the movement.

Then we have rond de jambe. Rond de jambe is unique because it basically connects the front, side, and back tendus without going through fifth position. This lets you practice the movement of your thighs going around in circular motion while keeping the turnout. And this is a very important element at this part of the barre because the combinations that come after rond de jambe must be an extension of it.

So what should you be thinking while you do rond de jamb?

Rond de jambe is the foundation for fondu, frappe, developpe…and more

Imagine doing a fondu to the front. But I want you to imagine what your thigh is actually doing rather than where your toes are:

We start from cou-de-pied. At this point, our thigh is actually in a le seconde. Let that sink in for a moment: Your foot may be physically at your ankle, but your thigh bone is in the position of being to the side in a la seconde. Then we carry our leg to the front, and that means we need to bring our thigh from a la seconde to the front. So in fondu to the front, you must actually do a rond de jambe to the front with your thigh.

And here is the important part that you cannot forget:

When you come back from front to cou-de-pied, you must again do a rond de jambe back to a la seconde with your thigh. Often I see that students are leaving their thighs to the front and bringing only the toes back to their ankle, making the transition completely turned in. When you come back to cou-de-pied the correct way, you are setting up fondu to the side correctly.

When we do fondu to the back, our thigh must do rond de jambe from the side to the back. The mistake I often see is that the thigh is unable to move behind the body, leaving the whole leg completely off center when finishing fondu back (a typical correction you might hear in this situation is “cross your leg to the back!”). And of course if you’re not crossing your leg to the back in tendu or rond de jambe, then this will be a problem for the rest of the ballet class.

The solution?

It is important to understand how to use hamstrings to carry your leg to the back. Often, many dancers use their gluteus, which makes the hip joints stiff, and end up in an un-crossed position. Or they may resort to twisting their lower back to make the leg appear to be crossed. When you first go into fifth position before you start a combination, you should already engage your hamstrings. You can even think of crossing your hamstrings to create fifth position (rather than turning out one foot and then the other). In this way, you can continuously practice using hamstrings during tendu combinations, or even before that in plies.

When you come out of back fondu, you must bring your thigh around to a la seconde as if you are doing a rond de jambe. I trust you are getting my point now, and you might be able to guess what I’m about to say about frappes…

Doing this might be a new movement pattern for you, which means you probably need to slow down a lot to practice this new coordination (and new thought process). Your thigh does rond de jambe, and if you think about your knee and lower leg, it has to bend and extend at the same time as your thigh going around. So fondu is rond de jambe with bending knees. Stop and read that line as many times as you need to before you continue.

Moving onto frappes and developpe: You guessed it, you must do rond de jambe with your thigh. And the important part is to never forget to make sure that your thigh is doing rond de jambe when you come out of front or back extension. Otherwise your working leg will be turned in, and that is not correct in any technique.

Circles in ballet are more important than you think

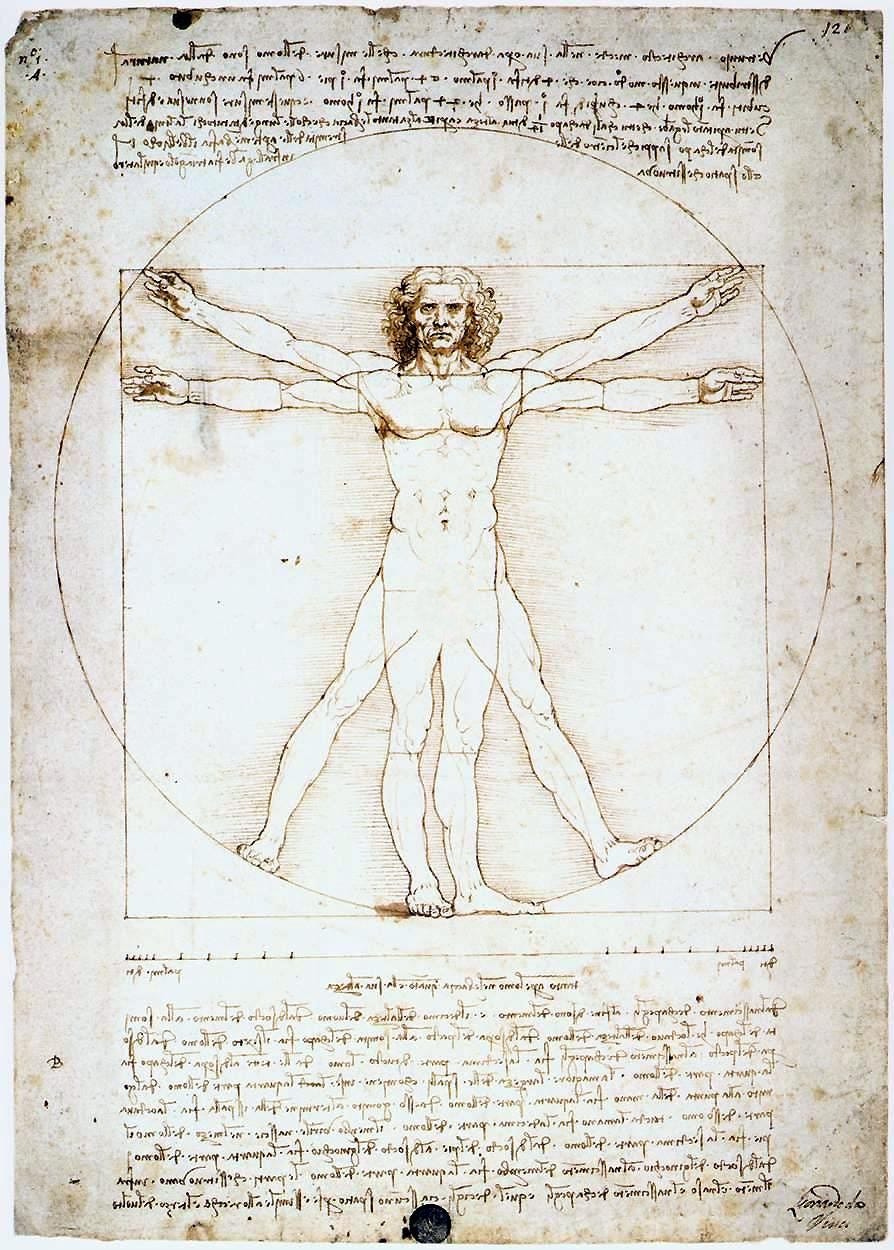

Remember, rond de jambe means “to round the leg.” The keyword here is round, and I want you to imagine the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo Da Vinci.

The picture itself isn’t telling us much. The notes below the image tell us some ideal proportions of a man. But what’s vivid is that the body parts—especially the legs and arms—are moving in a circle, and that is very important to understand for ballet dancers.

Ballet requires us to move our thighs, and those thighs must move in a circular motion. Once we can get that in our heads, we can effectively apply that to tendus, fondus, developpes, and grand battements. Even port de bras!

Too often we focus heavily on our feet, and we think that everything is linear movement. But this mistake leads dancers to try to make their lines “longer” (read why you may never want to do that), and they start to compensate in other parts of their body such as hips and lower back. They try to extend their feet as far as possible to make themselves feel like their legs are longer. In reality, that will lead to misalignment, which will often lead to injury. And actually, the farther you put your feet away from you, the shorter you will become.

So when we do tendus, our working leg thigh is moving in circles (and it is physically higher than the standing leg thigh). Then, when the tendu comes back into first or fifth position, it must essentially circle back down to the position.

Then the working leg thigh will be even higher in a degage exercise.

And anything above 90 degrees (like adagio and grand battement) will require the working leg to actually get closer to your torso, and not further away or “longer.”

How to create circles in fondu, frappe, and more

So now that you know your legs move in a circular motion, you have to think how fondu, frappe, and all the other steps can literally follow a circular path. Fondu, frappe, and other steps may look like they must follow a straight line. But using the circle idea will make much more sense for your body and ballet technique. Thinking about circular motion in your arms and legs follows your body’s more natural movement pattern. And in turn, you can create more power when you access your body’s natural motion (plus, less injuries!).

Circles in fondu: The goal for fondu is to finish both legs at the same time. That means both legs have a finishing point. Often the working leg goes through an under-curve to go out; however, fondu is an over-curve step, so there is a destination for the working leg. From cou-de-pied, you will lift your thigh up while in plie, then extend your working leg in a rainbow arc to go up and down to finish. Typically fondu is to do it at 45 degree height.

Circles in frappe: Frappe is a step that strikes the floor, so your leg will have to go through an under-curve aiming for the floor to strike. Then, because you strike the floor, the ending of your frappe will be off the floor. When you return to cou-de-pied, you must continue the circle going through an over-curve back to the standing leg. Often, frappe is taught to be just a straight and sharp out-and-in motion where the knee stays in place and the bottom half of the leg swings back and forth. It sure looks that way, doesn’t it? But that’s not what you should be thinking as you actually do it.

The ballet rule for thinking in circles and lines

Although almost everything follows a circular motion with ballet technique, sometimes you have to think in linear motion. So I have a good rule of thumb to know when to think in circles and when to think in lines. The rule is…if a movement appears to be linear (such as tendus and frappes), then think circles. But if the movement appears to be around (like rond de jambe or pirouettes), then think linear.

That’s the illusion of ballet: We create the visual of lines by allowing our body to move through a circular path. Or by creating beautiful circles when we think of lines.

In ballet, you need circles to create lines. And you need lines to create circles.

And like the Vitruvian Man, those shapes are beautiful.

Those shapes can create art.

I am always willing to work with people to clarify anything that is confusing, so there are many ways to contact me personally. You can comment, hit reply, or message me directly here. Also you can find me on Instagram.